The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law in August 2022 by President Joe Biden with the aim of accelerating the transition of the US economy to clean energy. Regrettably, it has also led to significant transatlantic tensions as the measures to encourage local manufacturing through massive tax credits is seen as protectionist, violating World Trade Organisation rules.

As an answer to the IRA, in early 2023 the European Commission presented an update to the European Green Deal, naming it the Green Deal Industrial Plan. The new plan repeats the 2050 climate neutrality goal of the continent, targeting the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) from 1990 levels by 55% by 2030. To achieve the goals, the European strategy relies on higher carbon taxes rather than large tax credits as well as showing a reluctance to include stronger protectionist elements, but instead reaffirms its intention to negotiate free trade agreements.

The sum of the Green Deal’s parts

The Green Deal Industrial Plan consists of two parts: the Net-Zero Industry Act and the European Critical Raw Materials Act. Together with the reform of the design of the electricity market, they provide a strong framework to reduce reliance on imports and increase the resilience of their supply chains. The objective is at the same time to accelerate the permit-granting process through introducing upper limits of a maximum of two years, down from current processes which could last up to seven years. A combination of state-aid rules and direct subsidies was put in place to secure the funding.

The Net-Zero Industry Act’s aim is to scale up the manufacturing of clean technologies in the EU, with at least 40% of the EU’s capacity needs by 2030 being manufactured locally.

The Net-Zero Industry Act’s aim is to scale up the manufacturing of clean technologies in the EU, with at least 40% of the EU’s capacity needs by 2030 being manufactured locally, while supporting the EU’s 2030 climate and energy targets and the 2050 net zero target. Wind turbines, heat pumps, solar panels, renewable hydrogen, batteries and CO2 storage are all in scope and the companies providing these technologies or part of their supply chain in the EU are poised to benefit. Notably for segments like solar PV1, the 40% target looks very ambitious as this would necessitate a significant expansion of the current nearly non-existent local production in a market of overall strong growth rates.

In the Critical Raw Materials Act, the EU is looking to ensure access to strategic and critical raw materials like lithium, cobalt and rare-earth elements through sourcing diversification and recycling, with the aim of boosting the EU’s security of supply. In addition, it includes a target that no single third country supplies more than 65% of any strategic raw material.

The European Green Deal also relies on the REPowerEU plan and the Circular Economy Action Plan. These were reset in 2022 to deal with the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The REPowerEU plan revolves around saving energy, diversifying the EU’s energy supplies and producing clean energy. While the first two parts have been largely successful already and helped avoid massive disruptions this winter, the increase in clean energy production is lagging. Therefore, on 30 March 2023, the EU Commission’s proposal to increase the target of renewable energy’s share of total energy use up to 45% in 2030 was agreed. This is a strong step up from the former target of 32% and compares to a 2022 level of 22%. According to the Commission, it would mean bringing the total renewable energy generation capacities to 1,236GW by 2030, from 475GW in 2021. While hydro capacity should not increase massively, wind and solar are expected to see a more than threefold increase from current levels. For this to happen it is now critical to see speedy action by each member state’s legislative framework.

While the long-term implications for the sector are overwhelmingly positive, the short-term legislative implementations in each market will be key. Faster permit-granting processes is the largest single driver for the change as, for example, there are currently c80GW of wind energy projects pending in permit-granting processes and it can take up to 10 years to grant a permit for a wind farm. With the strong decline in the technology costs continuing, however, the appeal of clean energy will grow for both the regulator and customers.

Sector-specific targeting

The revised directive now strengthens targets for buildings, industry and transportation. Building energy use is the largest sector in the EU, responsible for over 40% of energy consumption. The new indicative target of at least 49% renewable energy share in buildings by 2030 should strongly push member states to incentivise heat pump technology, one of the most efficient ways to lower energy use and raise green energy use via electrification.

Industry is included for the first time in the renewable energy directive with a 1.6% annual increase in renewable energy use and a 42% renewable hydrogen target (RFNBOs – renewable fuels of non-biological origin) in total hydrogen consumption by 2030.

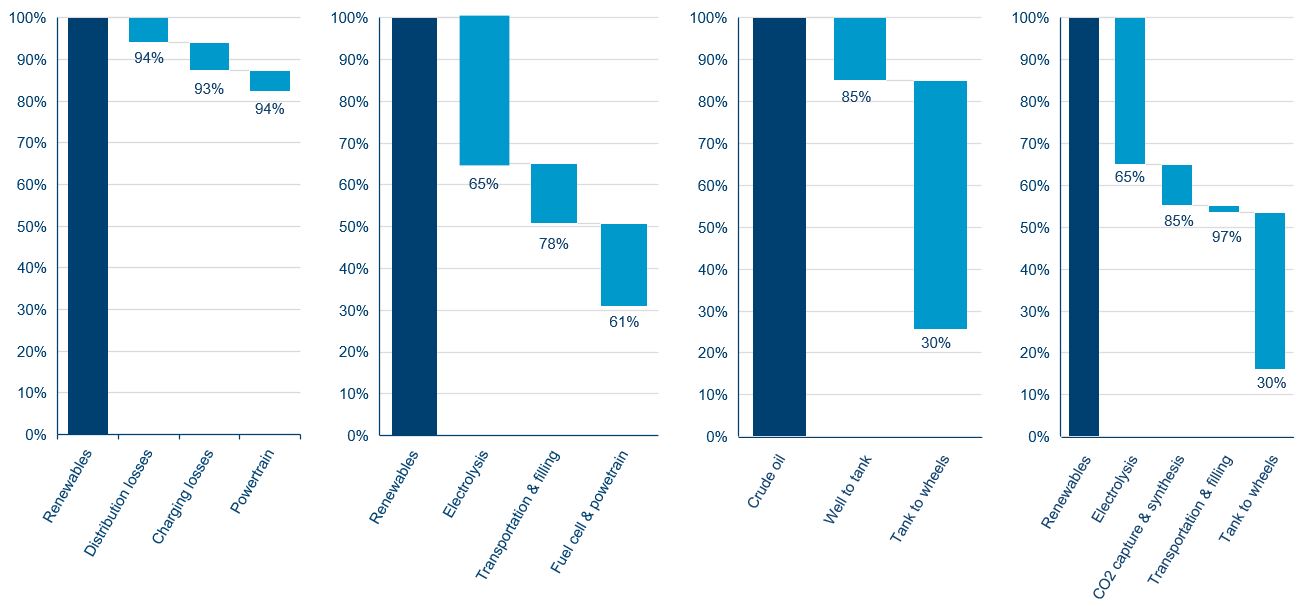

Transport is the second largest sector in terms of energy use and has seen a new framework for renewable energy: 14.5% GHG intensity reduction including a combined sub-target of 5.5% for advanced biofuels and renewable fuels with a 1% RFNBOs minimum. While we welcome the pressure on the transportation sector to move to green energy, synthetic fuels are a poor choice for passenger vehicles as they have a much lower overall efficiency than electric vehicles. They might be a decent choice for aviation, which has been the fastest increasing transport segment in the past few decades. Dedicating the 1% RFNBOs fully to the aviation sector would fill close to 10% of the fuel needs of that segment.

Source: Polar Capital estimates March 2023, Volkswagen: “Hydrogen or battery? A clear case, until further notice”, 7 November 2019; Siemens: “Efficiency – Electrolysis White paper”, 2021; fueleconomy.gov, as at 1Q23. Note: BEV = battery electric vehicle; FCEV = fuel cell electric vehicle.

With these new targets and the establishment of the European Hydrogen Bank, hydrogen becomes a clear pillar of the EU green energy framework. This newly established bank will help accelerate investment and cover the cost gap between green and grey hydrogen via a €/kg payment for 10 years based on an auction system, with the program expected to start in autumn 2023. To reach the 10 million tonnes of domestic renewable hydrogen production as planned by 2030 the necessary investments estimated by the EU are €335-471bn including €200-300bn for additional renewable energy production, representing a significant growth driver for the leading companies in that area.

Overall, the European Union’s Green Deal should lead to a tremendous increase in renewable capacity and green hydrogen production, though many hurdles still remain to be cleared. We expect a great deal of simplification in the legislative and permit-granting process to come through this year and next, leading to real momentum for all the companies active in these exciting sectors.

1. PV = photovoltaics